The Evolution of Radio, TV, and Online Media in Ghana and Nigeria

- orpmarketing

- Jun 4, 2025

- 6 min read

Pre-Colonial Roots: The Oral Tradition

Before radio waves crackled through the air, communication in Ghana and Nigeria thrived on oral traditions. In pre-colonial Nigeria, griots—skilled storytellers and historians—preserved cultural heritage through vivid narratives, passing down legends and histories. Drumming, town criers, and smoke signals relayed messages across communities, fostering unity and identity. Similarly, in the Gold Coast (modern-day Ghana), traditional rulers and storytellers used local languages like Twi, Ga, and Ewe to share knowledge. These indigenous systems laid a foundation for mass communication, their influence lingering in today’s storytelling-heavy media culture.

Colonial Era: Radio as a Colonial Tool

Radio arrived in West Africa as a colonial instrument, designed to connect empires to their outposts. In Ghana, then the Gold Coast, Sir Arnold Hodson, the colonial governor, introduced Radio ZOY on July 31, 1935, to mark King George V’s Silver Jubilee. It primarily relayed BBC broadcasts to colonial residents and elites via wired loudspeakers, a clunky setup that felt more like a megaphone for British propaganda than a public service. In Nigeria, the Radio Diffusion Service (RDS) launched in 1933, also piping BBC content to loudspeakers for expatriates and a select few locals. These services were less about informing Africans and more about keeping the colonial machine humming.

World War II changed the game. By the 1940s, colonial powers needed African support for the war effort, so they introduced broadcasts in local languages like Hausa, Fanti, Twi, Ga, and Ewe. In Ghana, B.S. Gadzekpo, a pioneering Vernacular Announcer, brought authenticity to these broadcasts, helping make radio relatable to local audiences. His memoir later documented the grit and creativity of early Ghanaian broadcasters, who worked in pairs to translate and deliver news in local tongues. Nigeria’s Nigerian Broadcasting Service (NBS), established in 1951 with BBC support, also leaned on local talent, with about 10% of its staff trained by the BBC to produce national programming.

But let’s not romanticize it—radio was a tightly controlled tool. Colonial censorship was fierce, especially in Nigeria, where journalists faced harassment or jail for criticizing authorities. The NBS was often seen as a mouthpiece for the colonial government, with figures like Governor John Macpherson using it to counter critics like Obafemi Awolowo, who called out colonial policies.

The Independence Era: Radio as a Nation-Building Force

As Ghana and Nigeria marched toward independence—Ghana in 1957, Nigeria in 1960—radio became a symbol of sovereignty. In Ghana, Kwame Nkrumah, the firebrand prime minister, transformed Radio ZOY into the Ghana Broadcasting Corporation (GBC), a public service broadcaster tasked with education, entertainment, and nation-building. Nkrumah’s vision was bold: he saw media as a tool to “conscientize” people, especially in a nation grappling with illiteracy. GBC expanded to include local language programming and cultural content, with 4,000 staffers shaping a distinctly Ghanaian identity.

Nigeria followed suit. The Nigerian Broadcasting Corporation (NBC), successor to the NBS, grew under post-independence leaders to cover the entire country. But freedom came with strings. Nkrumah in Ghana and successive Nigerian governments clamped down on dissent, with Nkrumah’s Preventive Detention Act and Newspaper Licensing Act wiping out private press by 1966. In Nigeria, the NBC often served as a government megaphone, especially under military regimes. Still, radio sets multiplied—by the 1960s, Africa saw a fivefold increase in radio ownership, from 90 to 450 sets per thousand people.

A standout moment in Nigeria was the 1959 launch of Western Nigeria Television (WNTV), the first TV station in Africa, spearheaded by Obafemi Awolowo and Chief Anthony Enahoro. This wasn’t just a tech leap; it was a political statement. Awolowo, premier of the Western Region, defied colonial resistance to create WNTV, dedicating 50% of its programming to education and celebrating local culture to counter colonial narratives. This sparked a regional TV race, with Ghana and other regions rushing to launch their own stations.

The Golden Age of Radio: 1960s to 1980s

The 1960s were a high point for African radio. In Ghana, GBC’s expansion into local languages like Hausa (a lingua franca in the north) and its focus on music and cultural programming made radio a household staple. In Nigeria, the Federal Radio Corporation of Nigeria (FRCN), formed from the NBC, became the country’s largest radio network, with FM stations in every state. Memorable voices like Raymond Dokpesi, who founded Ray Power in 1994 as Nigeria’s first 24-hour private station, began to challenge state dominance. Ray Power, alongside Wazobia FM, became a listener favorite, blending Pidgin English and local vibes to capture urban audiences.

Yet, this era wasn’t all rosy. In Ghana, post-Nkrumah regimes like Kofi Busia’s and Ignatius Kutu Acheampong’s swung between liberalizing and strangling the media. Busia sacked editors at the state-owned Daily Graphic for dissent, while Acheampong’s regime cut off foreign exchange to opposition outlets. Nigeria’s military governments were no better, with state-controlled media often drowning out independent voices. Still, radio’s reach grew, especially in rural areas, where battery-powered transistors became lifelines for news and entertainment.

Liberalization and the FM Revolution: 1990s to 2000s

The 1990s brought a seismic shift. Ghana’s 1992 constitution and Nigeria’s gradual media deregulation unleashed a wave of private stations. In Ghana, a 1995 protest over the seizure of Radio EYE’s equipment forced the government to issue FM licenses, birthing “broadcast pluralism.” By 2007, Ghana had 86 FM stations, with interactive phone-in shows in local dialects becoming wildly popular. Stations like Joy FM and Peace FM set the tone, mixing news, music, and talk shows in Twi, Ga, and English.

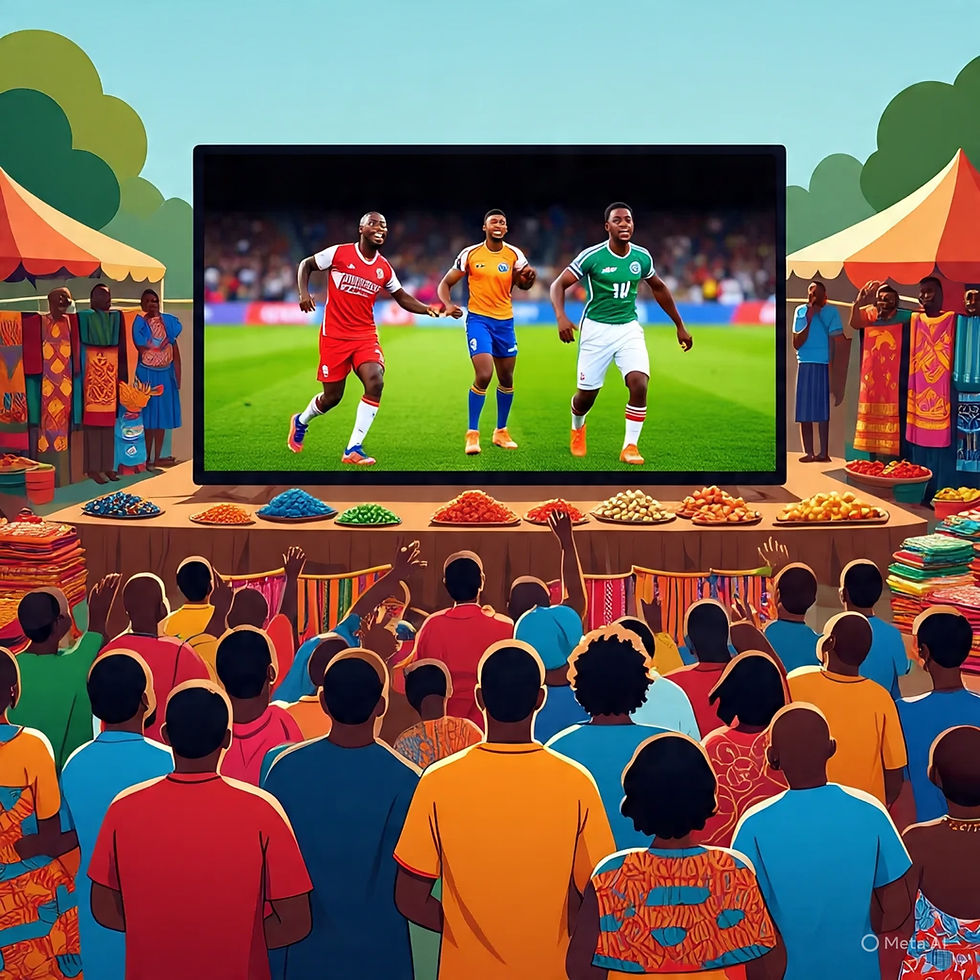

Nigeria’s airwaves exploded too. By 2022, Ghana had 513 radio stations, but Nigeria’s sheer size meant even more—each of its 36 states boasted at least one public and one private station. Wazobia FM and Ray Power topped polls, with FM dominating (90.4% of listeners) over AM or shortwave. Mobile phones became radio receivers, with 37.3% of Nigerians tuning in via their devices by 2015. Community stations like Lavun Community Radio gained traction, with shows like Gominati nya yina n letting listeners grill politicians live on air.

TV also matured. In Ghana, TV3 and Metro TV (both launched in 1997) challenged GBC’s monopoly, while Nigeria’s Nigerian Television Authority (NTA) faced competition from private channels like AIT and Channels TV. These stations brought slicker production and bolder journalism, though political interference persisted.

The Digital Age: Online Media and New Challenges

The internet flipped the script. By 2023, Ghana had 23 million internet users and 6.6 million social media users, while Nigeria’s digital boom saw platforms like Nairaland and Linda Ikeji’s blog rival traditional media. Radio adapted, with stations streaming online and launching podcasts. In Ghana, Citi FM embraced digital, blending radio with online content, while Nigeria’s Cool FM and Nigeria Info leveraged social media for listener engagement.

But it’s not all smooth sailing. In Ghana, journalists face low pay, bribery risks, and occasional violence—think Ahmed Suale’s unsolved 2019 murder. Nigeria’s media grapples with similar issues, plus disinformation on social media. Both countries rank high for press freedom (Ghana 9th in Africa, Nigeria lower), but political and business interests often muddy the waters. Community radio, like Nigeria’s Lavun, struggles with funding, while state broadcasters like GBC and FRCN face accusations of bias.

Memorable Names and Scenes

Kwame Nkrumah (Ghana): His media infrastructure, like the Ghana News Agency and Ghana Institute of Journalism, set the stage for professional journalism.

Obafemi Awolowo (Nigeria): His WNTV launch was a defiant act of cultural and political assertion.

B.S. Gadzekpo (Ghana): A trailblazing announcer whose memoir captured radio’s early days.

Raymond Dokpesi (Nigeria): His Ray Power broke the mold for private broadcasting.

Wazobia FM (Nigeria): Its Pidgin English broadcasts made radio feel like a street corner chat.

Joy FM (Ghana): A pioneer of private radio, blending news and entertainment with flair.

FESTAC ’77 (Nigeria): This cultural festival boosted TV content, showcasing African arts globally.

Institutions Shaping the Landscape

Ghana Broadcasting Corporation (GBC): From Radio ZOY to a national broadcaster, it’s been a cornerstone despite funding woes.

Federal Radio Corporation of Nigeria (FRCN): The backbone of Nigeria’s radio network, with stations in every state.

Nigerian Television Authority (NTA): A giant in TV, though often criticized for government leanings.

Daily Graphic (Ghana): The only truly national newspaper, a print media stalwart.

Ghana Institute of Journalism: Africa’s first journalism school, training generations of reporters.

The Present and Future

Today, radio remains king—80% of Ghanaians and 77.4% of Nigerians tune in weekly. But TV and online platforms are catching up, with social media driving public discourse. Challenges persist: funding, political pressure, and disinformation threaten media integrity. Yet, the legacy of griots and town criers lives on in the storytelling ethos of stations like Wazobia FM and Joy FM. As AI and streaming reshape the landscape, radio’s adaptability—seen in its leap from loudspeakers to smartphones—ensures it’ll keep humming in African homes.

Comments